|

Andrew Mcintyre chronicles the life and work of an early female photography pioneer and dog breeder

CHRISTIAN CAMERON-HEAD OF INVERAILORT

After the usual dancing in the drawing-room, they walk in solemn procession to the barn where the servants’ dance is going on. There they are not allowed a moment’s rest. From ten till 12.30 they dance reels steadily with one break in the shape of a country dance and another of Gaelic songs. The chief feature in the latter seems to be holding pocket handkerchiefs and waving them in time to a monotonous howl which the singers seated generally on each other’s knees call a song.

Guest entry, Inverailort Diary, 12th Sept 1873.

UNTIL the early 1800s, Inverailort had been MacDonald and Catholic country and Jacobite sentiments would continue to enliven many an evening’s entertainment for several decades to come. In 1828 the estate was bought by Major General Sir Alexander Cameron, a remarkable soldier who, in 1800, recruited and led a band of 150-200 Highlanders south to Horsham in Sussex to the sound of bagpipes, forming a Highland company in the new Experimental Corps of Riflemen (95th Rifles). He went on to give distinguished service in a string of campaigns including Waterloo, in the course of which he became a close friend and advisor to Wellington. He died at Inverailort in 1850.

Alexander’s son Duncan died a quarter of a century later, leaving Inverailort to his 15-year-old daughter Christian. Technically, of course, she was a minor and a family trust was appointed to run the place until she was mature enough to take over. In practice she more than likely kept a firm hand on the tiller from the start, for she was a capable young woman with a gimlet eye that missed nothing and had a formidable talent for getting her own way. She was, moreover, a worker: the Lochailort archives for 1876-1878 list “18 volumes of notebooks including Address books, notes on English literature & English history and Dinners attended with guest lists”.

In 1888 the young heiress was finally left to “go it alone”. She was well equipped to do so and a couple of years later married James Head, an ex-army captain and director of several shipping companies. They became parents in 1896 when Christian gave birth to mixed twins (Frances and Christian), and in 1910 the couple amalgamated their surnames to Cameron-Head by Royal licence.

Throughout this period Christian ran Inverailort more or less single-handedly and her output of note books, directives and correspondences swelled to embrace the wide run of topics encountered daily on any Highland estate. Insurance, staffing, hydro-electric generation, salmon catches and even sheep stealing in Mallaig were all dealt with in her firm handwriting.

But running an estate was only part of it. She had been brought up with Drynoch Terriers from early childhood - they had been bred by her family since the 1700s when her forbears on Skye, the 5th and 6th Lairds of Drynoch, bred the first cream and white specimens from an earlier mongrel variety. By the early 1900s Drynochs had evolved to become a distinct breed - shortly to be known as the West Highland White Terrier, and formally classified as such by the Kennel Club in 1906.

Christian did nothing by halves. She joined the West Highland White Terrier Clubs of both England and Scotland as soon as they were formed and a year later swept the board at Crufts and other national events. Her idea of type was a fixed one - she sought a “strong, small-boned dog, small enough to go to earth, and strong enough to fight the quarry when he got there”. By 1916 this definition of the breed together with others she contributed had been absorbed into the authoritative Kennel Encyclopaedia and The Hippodrome (a London periodical) described her as a “foremost authority on the breed”.

Yet Christian had another equal passion up her sleeve that the Press seems not to have known about. For years she had been taking photographs and the quality of her images was so high that she could have turned professional at any time, had it suited her. As with her dogs, she somehow found the time and energy and commitment to sweep aside all obstacles and produce spectacular pictures.

Cameras of that era were not easy to use. They were clumsy and absurdly fragile and the image projected on to the focusing screen was upside down, back to front and so dim as to be invisible until all light was excluded using a black cloth. The fragile glass plates and the mysteries attending their processing in a darkroom were still far beyond the ken of most folk who could only stare in disbelief at the astonishing results.

Christian took to all this like a duck to water and by the time of her marriage she was scouring the country for suitable images to make. It was quickly apparent that she had an out-standing eye for composition -perhaps encouraged and nurtured to a degree by her near-neighbour, the famous artist and painter Jemima Blackburn of Roshven (See The Scots Magazine January 2004). She must soon have become a common sight with her black focusing cloth and tripod, and doubtless had a favourite horse she would saddle up for more distant excursions.

The results were wonderful. Christian’s self-discipline and obsession for “getting things right” are apparent in nearly every picture she took. Photography of that era was essentially Still Life. The emulsions and lenses simply couldn’t cope with even slight movement during the lengthy exposures demanded by the process. Yet this was a minor limitation tor those raised in a tradition of canvas and paint and sessions lasting hours at a stretch. Sketching out a scene in advance, rehearsing the participants and posing them with care, was a familiar routine for any art apprentice.

But when we look back now from a modern era of “candid camera” and instant digital capture, those early efforts can seem almost laughably “staged”, which of course they were. How else could they have been done?

The other inescapable impression we get from Christian’s photographs is that she and her family spent the greater part of their lives stalking deer, going on picnics and taking the air in their steam yachts. The truth was somewhat different. These things were certainly done, but only as part of a hectic lifestyle that early cameras were ill-suited to record. It was, for instance, common for the head of the family to absent himself for weeks at a time on foreign business, leaving his wife to supervise the staff, pay the wages and deal with the many domestic crises that erupted.

Cameras were brought out when everyone had returned and there was a reunion to be recorded. The photographs provoked by these social get-togethers are fun to look at, but they are generally of less absorbing interest than Christian’s efforts at capturing the local countryside, often enlivened by inclusion of the people she lived and worked with on the estate.

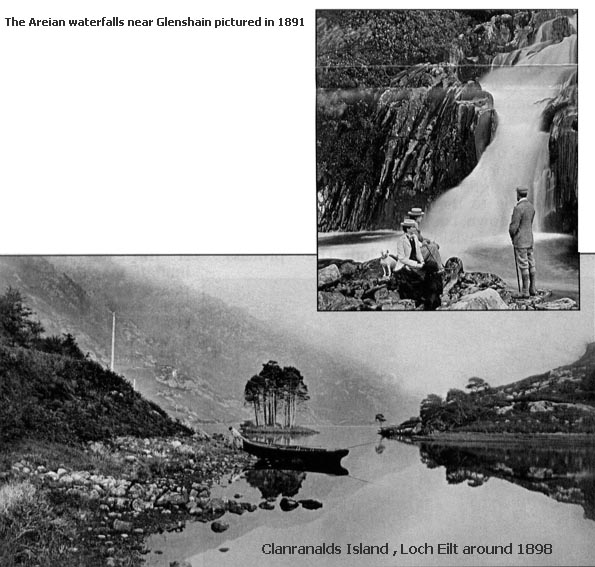

Her landscapes are unquestionably the best photographs she took. It seems nearly certain that she revisited the spots she was most drawn to and sketched her compositions on paper several times before returning with her camera. Her picture of a coal boat being unloaded at low tide, of three people (including herself!) grouped before a waterfall and of a young woman hauling a dinghy on to the shores of Loch Eilt all argue immense preparation and attention to detail. And she lived at a time before the landscape became scarred with railway viaducts, pylons and sitka plantations.

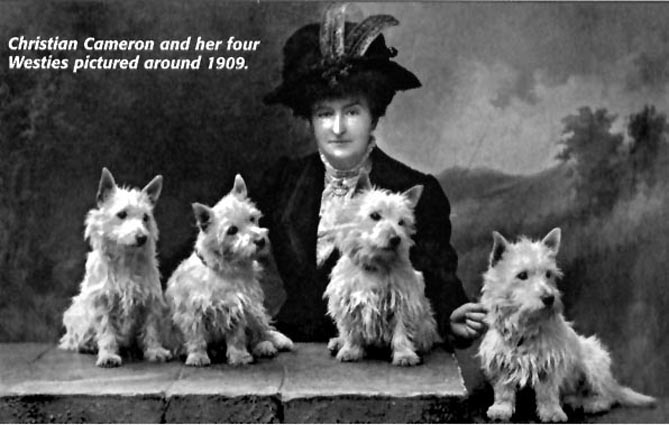

But there is more than a hint of vanity in her work, too, for she appears over and over again before her own lens, each time striking a pose in a different dress and no doubt using a passing child or ghillie to squeeze the bulb attached to the shutter. The most effective of these self-portraits is the one that has her in a feathered hat with her white terriers. It is exquisitely executed, for as always the composition was exactly right - but remarkably she also managed to capture all four dogs perfectly posed and perfectly in focus.

Christian’s life ended tragically during the Second World War. On 3rd June 1940 the MOD requisitioned her beloved Inverailort and turned it into a commando training base. It all happened with frightful suddenness as she was returning home from a trip to London. “I found both my houses (Inverailort Castle and Glenshian House) taken by the military and vans carting the furniture away out of both,’ she wrote in a distressed letter to her Edinburgh solicitor. “I am waiting here for a few days till I try to see what is happening to my clothes.. . there are to be 300 soldiers in the Castle and they have taken land on which to erect huts.” She never recovered from the shock and died the following year.

An exhibition of Christian’s photography is being staged during June at Resipole Studios, Ardgour, under the direction of the West Highland historian lain Thornber. lain has been involved with the Inverailort archives for most of his working life, dating back to a spell he spent on the estate in the late 1970s. At that time he received “enormous encouragement and support” from the late “Putchie” Cameron-Head of Inverailort (otherwise known as Mrs C-H), and following her death in 1992 he has assisted Highland Council archivists to sort and catalogue the estate records now held in Inverness.

Iain is using the occasion of the exhibition to produce a short biography on Christian, together with historical background information on the Cameron-Head family and Inverailort. He has also succeeded in identifying the locations at which Christian took her photographs and has put names to many of the faces.

Modern digital techniques can perform wonders on archival images and it has been possible to assemble around 50 enlarged gallery prints with a quality and sharpness that significantly exceeds anything Christian could have produced in her lifetime. For decades, the amount of detail a whole-plate negative captured ran far ahead of what could be seen in the final print. We can now reveal that detail with high-resolution scans and reproduce things that were invisible even to Christian’s gimlet eye. She would be thrilled to know how good her images really were!

* Published in Westie News “ Dec 2007” for The West Highland White Terrier Club Of England

|